Economic and market conditions look very bad. Consider the following news items:

While U.S. auto dealers expect to sell around 9 million cars by the end of this year, the performance will be a 23% drop from last year—the largest annual percentage erosion in any year since 1958. For next year, the outlook is no brighter.

The depression in the housing industry has had a double effect. Many people who want to buy a house now find that it is either beyond their

means or they cannot find a mortgage for it.

The current recession has also shown a greater capacity to frighten the public than any of the previous postwar downturns. The next report of the University of Michigan’s respected Survey of Consumer Confidence, due this week, will show the deepest pessimism about the economy since the survey began in 1946.

Conditions like these fray even the steadiest nerves. With news like this, it is easy to fear that we are facing another Great Depression. But the news items above come from the 1974 recession, right around the time that the stock market hit its lowest point. They are strikingly similar to today’s headlines.

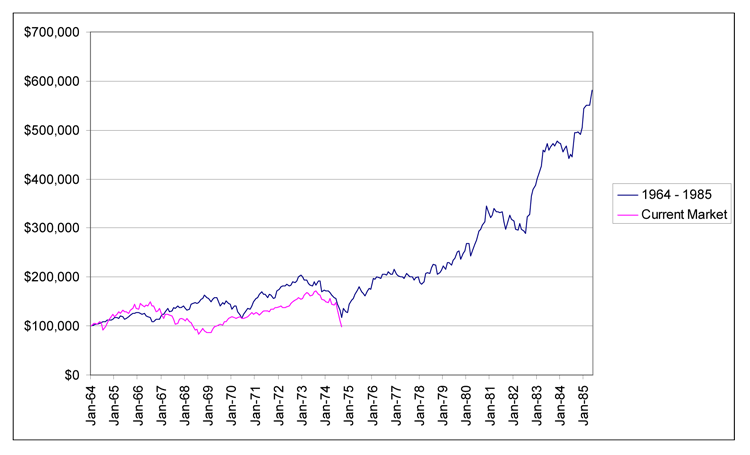

So we thought it would be helpful to take a look at stock market results for the 10 years before the depths of that recession, and 10 years following.

The blue line represents the S&P500 from January 1964 to May of 1985. The pink line represents the S&P500 from February 1998 to present. Notice that in both cases, a $100,000 investment would have been worth close to $100,000 after 10 years. However, from the depths of the bear market in 1974, the next 10 years resulted in a gain of 400%, which is an annualized return of 16.2%, and took the $100,000 to almost $600,000.

While no two time periods are exactly alike, 1974 turned out to be the greatest opportunity for stock investors of that generation. We think the odds are also very good for strong returns in stocks over the next several years.

Of course if this is such an opportunity, only those investors who stay committed to being invested will reap the rewards. There are several factors that can cause an investor to sell when they should be holding or buying.

Forced Out

If an investor is not able to stay invested because they need to withdraw money for their expenses, then they can be forced out at low prices. This risk can be minimized by aligning your stock allocation with your risk capacity. Your risk capacity is measured by relating your future investment cash flows to your total portfolio. For example, if you are able to add money to your investments, you can be buying stocks and therefore can have a high allocation to stocks. If you must withdraw funds for expenses, then you should have a lower allocation to stocks so that you will not be forced to sell at low prices.

Of course in times like these it can be prudent to reduce spending where appropriate. Extra income, if it is an option, can also provide a further cushion against forced sales at current low prices.

Scared Out

Emotions are not helpful when it comes to investing. The reason is that prices become low when most people are afraid, and prices become high when most people are fearless. So naturally most people must do the wrong thing at the wrong time, or prices would never be too low or too high. You’ve hired us to worry about your investments, which we do all the time, so as long as you are keeping us up to date on your situation we’d encourage you to live your life by focusing on people and experiences that are most meaningful to you.

Faked Out

The shorter the time period that you focus on, the higher the degree of unpredictability in the market. That is why it is important to understand that most of your investments are invested for the long term, so while someone may think they know what will happen to the market in the next three to ten days or weeks, we know that it is much more important and helpful to think about where the market is likely to be in the next three to ten years.

This prevents the mistake of selling all stocks because you are sure they are going down, and then realizing that you have a tough decision to make- when to buy back. Unfortunately if the market does decline, it reinforces confidence that you are right and the most common mistake is that the buy back price almost always continues to fall with the market, so most investors who attempt such an all or nothing strategy end up being faked back in at higher prices. This common mind game is why we use an allocation range for stocks so that we are not in an “all

in/all out” position.

We are not immune to the risk of overconfidence or thinking that our hindsight is the same thing as a crystal ball, which is why all of us use exactly the same process, strategies and reviews that you have. We are all FSI clients.

Worn Out

This is a common mistake after an extended period of poor results for stocks which is exhausting.

Early in my career in 1985, I remember a meeting I had with a prospective client. I asked them whether they had ever invested. They told me that they had invested in a stock mutual fund beginning in the mid 1960’s and after ten years their returns were lower than if they had put the money in the Credit Union, so that’s where they moved their money, and where it had been up until 1985. Essentially they remained invested during the prolonged sideways market, but sold out before the market went on an extended climb, thereby feeling the pain but receiving no gain.

I’m sure this was not an isolated case at that time, as 1974 must have felt very much like today